“It was time to champion our own sound”

Thirty years ago Blur released Parklife and ‘Britpop’ went mainstream. But there’s a secret history to be told that shows the era was far more varied and inclusive than it is given credit for

On the 25 April 1994 – that’s three decades ago, folks – Blur released their third album Parklife. It was a critical and commercial success, gaining plaudits from all corners of the media as well as going straight to number one. It stayed on the album chart for 90 weeks, went on to sell over a million copies in the UK alone, and was the first in a run of albums from UK acts that wouldn’t have got anywhere near Top of the Pops 18 months previously. Its release marked the moment a musical movement, formed in the dingy clubs and pubs of the capital, moved unequivocally into the mainstream. For some this may have been perceived as a victory, a validation of sorts, but for those who were there at the beginning it was as perplexing as it was unprecedented. The tiny scene that encompassed lounge soundtracks, lo-fi electronica, retro pop and spiky post-punk found all its subtleties and nuances planed off and branded ‘Britpop’, which then became a byword for bloated 90s major label excess.

This laddish, boozy, boorish image has gone on to taint the music, yet the seeds of what became Britpop took root in an art school sensibility and DIY aesthetic. Back in 2020 DJ, writer and curator Martin Green put together Super Sonics – 40 Junkshop Britpop Greats a compilation which aimed to reacquaint the public with the origins of the scene, and reinforce the outsider status of many of the acts. Green was the driving force behind Smashing, one of the London clubs the epicentre of early 90s home-grown creativity.

“The impetus for Smashing was to play out records that you wouldn’t hear anywhere else and to mix up lots of different styles,” says Green. “Up until then clubs didn’t really do that, they would tend to play one type of music, but we would play punk to easy-listening to disco to glam, all kinds of funny things really.” There were plenty of takers for this mix-and-match approach. “Most of the crowd were in their early 20s and there was definitely a diversity to it all – we’d have people like Leigh Bowery and Jarvis Cocker on the dance floor. It was very mixed and very inclusive.”

By 1993 Smashing found a permanent Friday night home at Eve’s, a Regent’s Street club made famous by the Profumo Scandal in the 60s, and bands such as Suede, Pulp and St Etienne were regulars.

A couple of miles away in Camden another club was plundering the past to find a future. A bit more rough and ready and a lot less camp, Blow Up was the brainchild of Southend DJ Paul Tunkin.

“I felt something was missing at club level in London and we needed more pizazz, ambition, and energy.” Blow Up looked back musically, says Tunkin, to re-energise the present. “We played a variety of 60s music – soundtracks, beat, Hammond instrumentals, dancefloor jazz – alongside new wave, glam and indie to create a new swinging London.”

Always ready to name a scene, the 90s music press were quick to align these emerging cliques, whether the bands liked it or not.

“Our motives were quite pure at the time,” says Steve Lamacq, who in 1993 was Reviews Editor at Select magazine. “There were a lot of us who were fans of Blur and thought Modern Life Is Rubbish was a really underrated record. Although there was a lot of good stuff coming out of America, it was time to champion our own sound, as so much of it was being overlooked.”

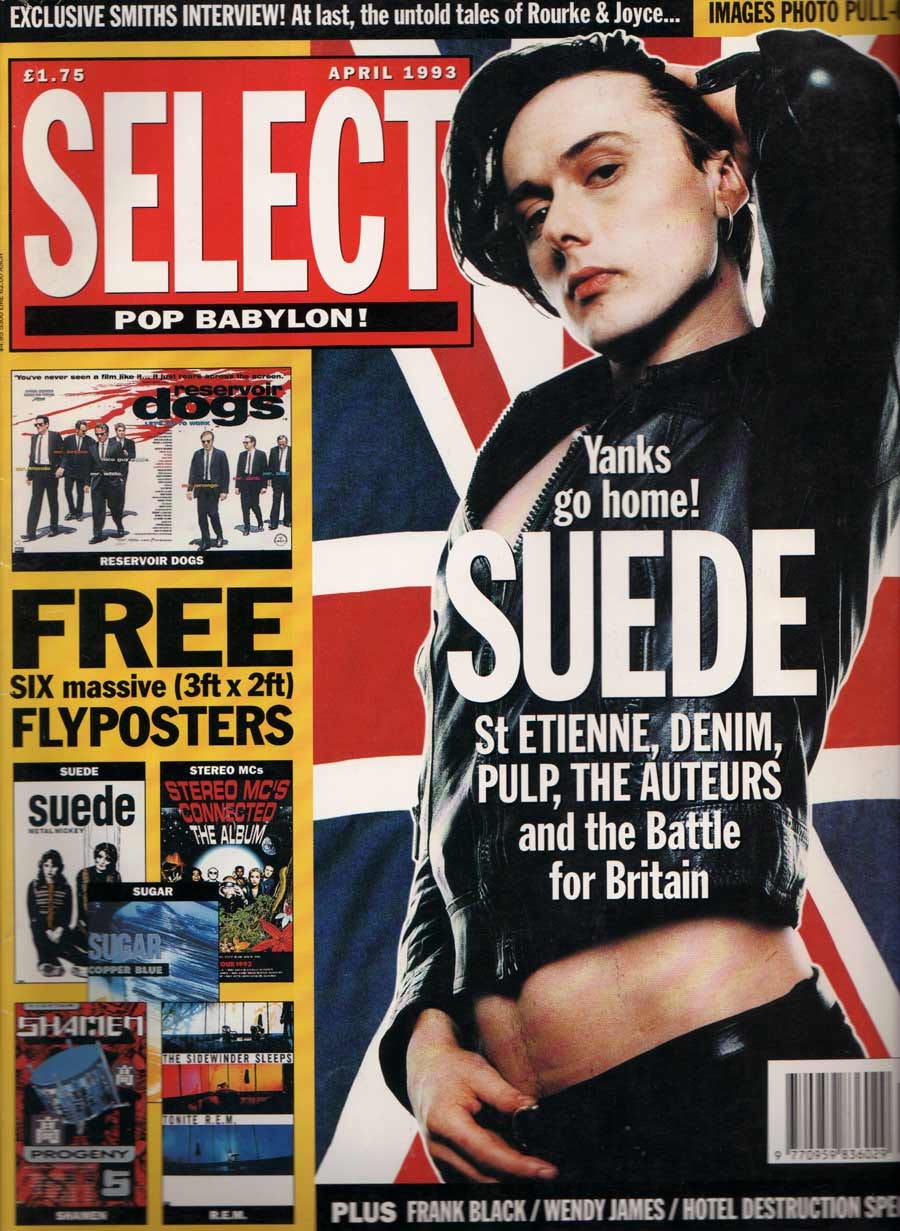

This championing was none more evident than on the April 1993 cover of Select, which featured Brett Anderson superimposed on the Union Jack, alongside the legend, ‘Yanks go home!’ For many, this was the starting point for Britpop, particularly as it was the first time the phrase was used to describe a group of bands including Suede, Pulp, Denim, St Etienne and The Auteurs.

Lamacq took his home-grown supporting stance with him to the BBC when he and fellow broadcaster Jo Wiley took over Radio 1’s Evening Session.

“Jo and I arrived at the perfect time,” he says, “The second half of 1993 Britpop was just beginning to reveal itself. I liked the mix of influences, lining up bands like Wire and The Kinks, and how it celebrated the different characteristics displayed by songwriters and lyricist around the country. You had the arch, observational, yet slightly cynical view from London; the big uniting anthems from Manchester; that post-Beatles maverick thing in Liverpool and a sort of west-coast Britpop from Glasgow. I wanted the Evening Session to be like the shows I’d listened to as a teenager, where you felt part of something, and Britpop gave us something to focus on, something to form a gang of listeners around.”

As Suede, Pulp, Blur and Oasis started their assault on the mainstream, a second wave came in their wake – groups such as Supergrass, Sleeper and The Bluetones. Bands also started to emerge featuring the DJs and regulars at Smashing and Blow Up, including Menswe@r, The Weekenders and Pimlico.

“It was good fun for the first couple of years,” says Lamacq. “There were indie clubs every night in London and there were loads of little victories, like Pulp’s Common People going to Number 2 in the chart. It really felt like the misfits were on a winning streak.” But then, says Lamacq, the record company cheque books came out. “Bands with limited talent were signing for stupid money and then making average records and you started to see the cracks in the scene.”

So, looking back three decades on, what is the real legacy of Britpop?

“The reinvention of the DIY scene was one of its triumphs,” says Lamacq, “Our postbag was full of self-financed singles and obsessive new fanzines.”

This is borne out by the Super Sonics compilation: for every Pulp, Blur and Elastica; there are multiple Scalas, Powders and Showgirls.

“Some of the bands forgotten in the mists of time certainly played a key role in the era,” says Tunkin, “As they helped to enrich the scene and culture, and injected ideas that were sometimes picked up by the better known acts.”

Using Green’s Super Sonics compilation as inspiration – and sticking to format du jour the 7” single – I outline the development of what became Britpop, from the late-80s progenitors, through early releases from the big hitters, to bands that barely made an impact even at the time.

“There was a spirit and an energy in the scene that is in these records,” says Green. “A lot of them still sound amazing. Nothing feels corporate or commercial, nothing is aimed at America or global success, which everything seems to be now. Just an explosion of creativity from unique and interesting people doing things on their own terms.”

Full disclosure: I was in one of the bands mentioned below. You’ll have to guess which one.

Boys Wonder / Goodbye Jimmy Dean / (Boys Wonder Records/BW1/7”/1988)

Predating the first mutterings of the label ‘Britpop’ by five years, Boys Wonder already had the template mapped out. “As far as a British band rejecting the perception of contemporary American culture, here’s your patient zero,” says Andy Lewis, resident Blow Up DJ and bassist with Pimlico, who would regularly drop Boys Wonder tracks into his sets. “They were so unfashionable in the 80s they were ahead of their time,” he says. “Had they been around a few years later they’d have cleaned up.”

Plundering the recent past and using it to comment on the contemporary became de rigueur in the 90s but by the time everyone had caught up Boys Wonder had morphed into Corduroy and were filling dance floors with a very different yet equally arch approach.

Five Thirty / Air Conditioned Nightmare / (EastWest/YZ543/7”/1990)

Another band who were a couple of years ahead of the game, Five Thirty came out of the 80s mod revival alongside The Prisoners, Purple Hearts and The Truth. Their adoption of 70s-referencing clothing and the psychedelic tinge of their power pop put them slightly out of step with their contemporaries and predated a lot of what went on to define 90s guitar music. Despite signing to EastWest in 1990 the band disbanded in 1992 and split into Orange Deluxe and The Nubiles, both bands finding favour with the Evening Session but not much beyond.

World of Twist / Sons of the Stage / (Circa/YR62/7”/1991)

Formed in Sheffield in 1985, it took World of Twist a while to get going, but once they did there was no one else like them. With louche singer Tony Ogden leading the charge, they mixed up space rock, psychedelia and northern soul, which combined with their papier mache and tinfoil stage props, made them unlike any band before, but plenty since. Unfortunately, they never managed to properly capture what made them special live in the studio, although early single Sons of the Stage comes close. I think it’s fair to say a pair of squabbling Mancunian brothers were listening.

Kinky Machine / Swivelhead / (Lemon Records/LEM 4/7”/1992)

Flying the glam-rock flag as early as 1991, Kinky Machine drew comparisons to Mott the Hoople and The Only Ones, and mined the same 70s seam as Suede and Pulp. “In the beginning I definitely felt we were going against the grain,” says main man Louis Eliot. “I had this Oxfam glam aesthetic in mind, not just visually but musically too; trying to match the melodic sensibilities of David Bowie, the storytelling of Ray Davies, the drum sound of the Glitterband and the backing vocals of Mick Jones. I was striving for a cultural identity that seemed diluted or completely forgotten.”

Eliot called time on Kinky Machine in 1995 but re-emerged a year later with Rialto, who Lamacq describes as, “One of the more underrated bands of the era.”

“Rialto had some almost comically bad luck with record company politics,” says Eliot. “We knew we'd made a great record but as well as everything else, you need luck and good timing.”

Pulp / My Legendary Girlfriend / (Caff Corporation/serial no/7”/1992)

Despite being included in the same issue of Select as new boys Suede, Pulp had been around in one form or another since 1978 and had already released three albums. My Legendary Girlfriend was something of a turning point for the band, originally released by Fire Records in 1991 it became a Single of the Week in NME. A 7” version a year later became the final single for Bob Stanley’s Caff Corporation label and features a BBC Radio 5 session version of the title track and two never-again-released bonus songs. “Pulp were the first Britpop band,” says Lamacq, “And My Legendary Girlfriend and Countdown were probably my first two favourite Britpop songs.”

Suede / The Drowners / (Nude/ NUD1 /7”/1992)

“In 1991 indie was completely PWEI, EMF, Ned’s Atomic Dustbin, all those crusty bands,” says Green. “Suede were the first indie band who rejected that.” In retrospect the ‘Best New Band in Britain’ hype surrounding Suede somewhat overshadows how genuinely exciting their first run of singles was. The Smiths and David Bowie were often mentioned reference points but their debut single The Drowners showed that they were already marking out a territory that was entirely their own. The B-sides – To the Birds and My Insatiable One showed this was no fluke, and Morrissey gave the band his seal of approval by covering the latter live.

Blur / Popscene / (Food/Food 37/7”/1992)

Released within weeks of Suede’s debut, the fate of Blur’s first step away from the baggy sound they were known for couldn’t have been more different. Stalling at number 32 it was panned by the music press and follow up single, Never Clever, was shelved completely (a studio version can be found on the Food100 compilation). Its failure only made the recalcitrant Albarn double down on his band’s ‘Britishness’ and Blur’s second album Modern Life is Rubbish (working title Britain Vs America) became a touchstone for the burgeoning movement. Popscene is now rightly recognised as classic and, along with The Drowners, is often referred to as the first Britpop single.

Stereolab / French Disko / (Duophonic/D-UHF-D03/7”/1993)

“Britpop may have been pro-British culture,” says Green, “But in an inclusive way, more of a European Britishness. The two things most bands who came from the scene had in common were they were art school kids and they loved Stereolab.” The English-French avant-pop band formed in 1990 and their combining of lounge, kosmische and 60s pop seemed tailor-made for what was happening in London at that time. “We used to play French Disko and Ping Pong at Blow Up! all the time,” says Lewis. “They didn’t really sound like anything else; they were ram-raiding pop culture, helping themselves, it was very post-modern.”

Elastica / Stutter / (Deceptive/BLUFF 003/7”/1993)

Justine Frischmann’s role in the development of what became known as Britpop is shamefully underestimated. The ideas of Britishness that started with Suede went with her to Blur and the uniform of 70s-referencing clothing (Fred Perry’s, DMs, vintage sportswear) that defined the Britpop era came directly from her social circle. Even the resurgence of the 7” single can be traced back to Frischmann.

“I’d started a label and Justine got in touch,” says Lamacq, “We went for a drink and talked about putting a 7” single out as Elastica’s first release. Remember, this was a time when vinyl had fallen dramatically out of fashion. But we did it and within the year, everyone was turning back to vinyl, there were limited edition 7” singles all over the show.”

Tiny Monroe / VHF 855V / (Laurel/Laurel 1/7”/1993)

Lumped in with the short-lived New Wave of New Wave (NWONW) mini-movement, Tiny Monroe formed in London in 1993 around statuesque singer and guitarist NJ Wilow. Although there was definitely a touch of Suede about them, NJ’s natural charisma leant them a haughty glamour that recalled 70s Roxy Music. Their debut single, a paean to NJ’s Ford Escort, VHF 855V was released on faux-indie label Laurel (in fact a subsidiary of London Records) and should’ve set the band up alongside other former NWONWers Elastica and Echobelly. However, line-up and label wrangles meant when their debut album Volcanoes did eventually arrive three years later it promptly disappeared without a trace. This spiky single, and its more measured follow up, the Cream EP, show what might have been.

Showgirls / Saturation Saturday / (Explosion Records / EXP 001 / 1994)

Showgirls hailed from Newcastle and were fronted by platinum blonde Justine Grimley. They released five singles of spiky power pop (four of them on music industry stalwart Tot Taylor’s Poppy records) but the promised album never materialised and the band split in 1997. Their debut self-released single Saturation Saturday put them in the same category as Elastica and Echobelly, although not the same league.

The Weekenders / All Grown Up/Househusband / (Blow Up/BLOWUP001/7”/1994)

For Tunkin his band The Weekenders went hand in hand with Blow Up. “Both were concepts working towards similar goals,” he says, “And we fulfilled a lot of our objectives to some extent. All our singles had sold out of their pressings and things were seemingly moving up.” A combination of bad luck and logistics meant album sessions were aborted. “By the time the band was once again operational, I was working on moving Blow Up from Camden to Soho so my hands were full. Plus, I felt the moment had gone to some extent.” The band left three 7”s celebrating Tunkin’s vision of a 90s swinging London, of which this was the first.

Nancy Boy / Johnny Chrome and Silver / (Equator/NBOYS001/7”/1994)

Not all Britpop was from the UK. Nancy Boy featured Hollywood nepo babies Donovan Leitch and Jason Nesmith (their dads were folkie Donovan and the Monkee’s Mike Nesmith) and they took a distinctly Anglophile approach to their own music. Part Blur, part Gary Numan, totally Britpop, they were completely out of step at home in America but were embraced by the scene in London. “They fitted right in at Blow Up,” says Tunkin. “The club had moved to the Wag in Soho when they played, and Mick Jagger turned up to see them and had a shake on the dancefloor.”

Blessed Ethel / Rat / (2 Damn Loud/2DM04/7”/1994)

Two years before the Blur vs Oasis spat the Mancunians were locked in another battle for supremacy, this time at Manchester’s In the City live event, against NWONWers Blessed Ethel. Again, the Gallaghers had to settle for second place. “We played this a lot on the Evening Session,” says Lamacq. “It had traces of the NWONW and obviously an affection for Pixies and American alt-rock, but still fitted perfectly into the wave of bootgirl-Britpop that I always associate with DMs, charity shop clothes and hollering choruses.” Unfortunately for the Malvern-based four-piece, Oasis may have lost the battle but won the war, and their meteoric rise inversely mirrored Blessed Ethel’s return to obscurity.

The Bluetones / Slight Return / (Superior Quality/TONE 001/7”/1995)

“In the band’s formative years there were lots of cool things happening around London, particularly Blow Up,” says The Bluetones vocalist Mark Morriss. “It was like a disco with a live band in the corner. There was probably only 60 or 70 people there but it was really good.” It was at gigs like this the band sold a self-financed blue vinyl 7”, limited to 2,000 copies. “It was just something that people could take home from a gig really,” says Morriss, “But it got picked up by John Peel and he played it on his show a few times and that’s when the labels started turning up. After that there was a lot of wooing and a lot of wining and dining.” That first single featured an early version of Slight Return, a song that would be reissued and reach number 2 in the charts just over a year later.

Powder / 20th Century Gods/Dizgo Girl / (Parkway Records/PARK001X/7”/April 1995)

Powder only stuck around for three singles, all released in 1995, but they still manged to get themselves on the BBC’s Britpop Now special alongside the era’s biggest names. This may have had something to do with them being signed to Parkway Records, the label run by Savidge & Best, the PR company who looked after many of the acts who appeared on the show. Not to take away from them as a band, Green recalls singer Pearl Lowe being a central figure on the scene and describes the band as, “A tremendous punch of powerhouse pop.” 20th Century Gods was their first single and all 1,500 copies were sold within two days of its release.

Kenickie / Catsuit City EP / (Slampt/ Slampt 31/7”/1995)

Saint Etienne had a pivotal role to play in the careers of several bands on this list. Whether releasing singles on their Caff and Icerink labels or simply championing them to anyone who would listen, Britpop as we know it owes them quite the debt. One of those bands was Sunderland’s Kenickie, who went from scratchy lo-fi beginnings to bone fide chart hits. “They were the ones who made it to TOTP,” says Green. “They eventually signed to EMIDISC and released a few terrific 45s and two albums before splitting in 1998.” The sleeve of their debut EP on Slampt features a drawing of the band by singer and guitarist – now broadcaster and writer – Lauren Laverne.

Alvin Purple / Headcase / (La La La Land/LALA005/7”/1995)

Straight out of Harrow, this three-piece didn’t stick around for long. Having one track on Fierce Pandas’ Return To Splendour EP they released their sole single – on purple vinyl naturally – on the label who brought the world Ash. Produced by the legendary Clive Langer and Alan Winstanley (Madness, Teardrop Explodes, Dexy’s Midnight Runners) Headcase is a glam stomper with a 70s kids’ TV theme interlude, while the B-side namechecks Carry On… actor Jim Dale to cement the retro references. A few gigs were played in support of the single and then they were gone.

Menswe@r / I’ll Manage Somehow / Laurel / LAU4 / 7” /Apr 1995)

Probably the most the most divisive act to come out of the era, Menswe@r are arguably better known for what they did before they released a record than after. Regulars at both Blow Up and Smashing, they formed at the former and played their first show at the latter, causing a bidding war between labels desperate to sign the next Pulp or Blur. “We got a £590,000 publishing deal for three songs,” says Menswe@r vocalist Johnny Dean. “In retrospect it wasn’t a great idea to take all that money, but back then it was all about the bravado.” The resulting single – which they played on TOTP before it had even come out – was hardly revolutionary but captured something of the time and quickly sold out of its 2,500 pressing. “We were kids and we wanted to have some fun,” says Dean, “That’s what Menswe@r were about, we were saying, ‘Look what’s possible.’”

Shag / The Shag EP / (No Label/No Cat No/7”/1995)

Many pre-existing bands had their heads turned by Britpop’s unstoppable rise and before long they were cutting the excess from their music as well as their hair. Accusations of bandwagon jumping abounded, but Lewis is more sanguine: “They were mirroring what was going on every week at Blow Up where bands would come down to see what the fuss was and then come back the next week a little less hairy.” As St Albans four-piece Shag looked to the late-70s for inspiration, they found they had a talent for 3-minute new wave pop songs, as evident on their impossible to find debut EP. “Time has been pretty kind to this,” says Lewis. Managing to make it onto the Evening Session, only 250 copies were pressed and only one copy has ever appeared for sale on Discogs.

Perfume / Lover / (Aromasound/AROMA003/ 7”/1995)

Perfume rose from the ashes of Leicester’s Blab Happy and initially self-released singles on their own Aromasound label. 1995’s Lover caught the ear of the Evening Session and became a firm favourite of the show, with Jo Wiley describing it as, “The sweetest song in all the world.” The band toured with the likes of Gene and Travis and eventually signed to Big Life who reissued the single in 1997. “This is one of Britpop’s early great lost hits,” says Lamacq, “A wonderfully romantic jangling stomp of a single which captures the more wistful strumming side of the genre.”

Pimlico / Bubbles/Fanciful / (Vinyl Japan /PAD32/7”/1996)

“There was an excitement to bands appearing from nowhere with one 7” and then disappearing,” says Lewis, “Although the downside is they never got to develop beyond that initial rush.” Wary of that, for their third single Lewis’ own band Pimlico moved on from the power pop of their first EPs and broadened their musical palette. Bubbles is a highlife-influenced calypso while double-A-side Fanciful a frantic brass-driven dash. Their debut album stretched the sound further, taking in psych and chamber pop, but due to label issues, it took another two years for it to be released, by which time any band associated with the Britpop tag were persona non grata and it joined an ever-growing list of lost albums of the era.

Slater / Random Acts of Senseless Violence / Dry Records / DRY001 / 7” / 1996)

“So many bands were throwing stuff out there and seeing what happened,” says Lewis, “It’s almost impossible to find out anything about them now.” The missing link between Pulp’s kitchen sink lyricism and Blur at their punkiest, the scarcity of Slater’s sole release makes it hard to find even in this day and age of YouTube. “There were a lot of bands who had more enthusiasm than ability and Slater definitely fell into that camp,” says Lewis, “But that’s what was great about the time, bands were buoyed along on the energy of it all, and there was an appreciative audience for them.”

Martin Green’s excellent compilation Super Sonics – 40 Junkshop Britpop Greats is available from Cherry Red Records here.

For those who read to the end…

The Dancing Architect has been going for a couple months now and the feedback has been really positive. So thanks to everyone who’s subscribed, and an extra-special thanks to those who have contributed financially.

The Dancing Architect will be taking a week off next week – I’ve got some freelance deadlines coming up, so I need to focus on those and keep my commissioning editors happy. Please do dig into the archive posts – all eight of them – and feel free to like and share them.

There’s plenty of stuff in the pipeline, including some interviews that will be new and completely exclusive to this Substack – the first of those will be posted in early May. I haven’t decided whether or not to make those available to paid subs only – obviously I want to share my writing with as many people as possible, but I feel those who are contributing to the costs of running this should be rewarded in some way. There are a couple of different paid subscriber options, so please consider one them if you like what I’m doing here.

For the time being though, The Dancing Architect remains free for all, so do catch up on past posts and let me know what you think.

Cheers!